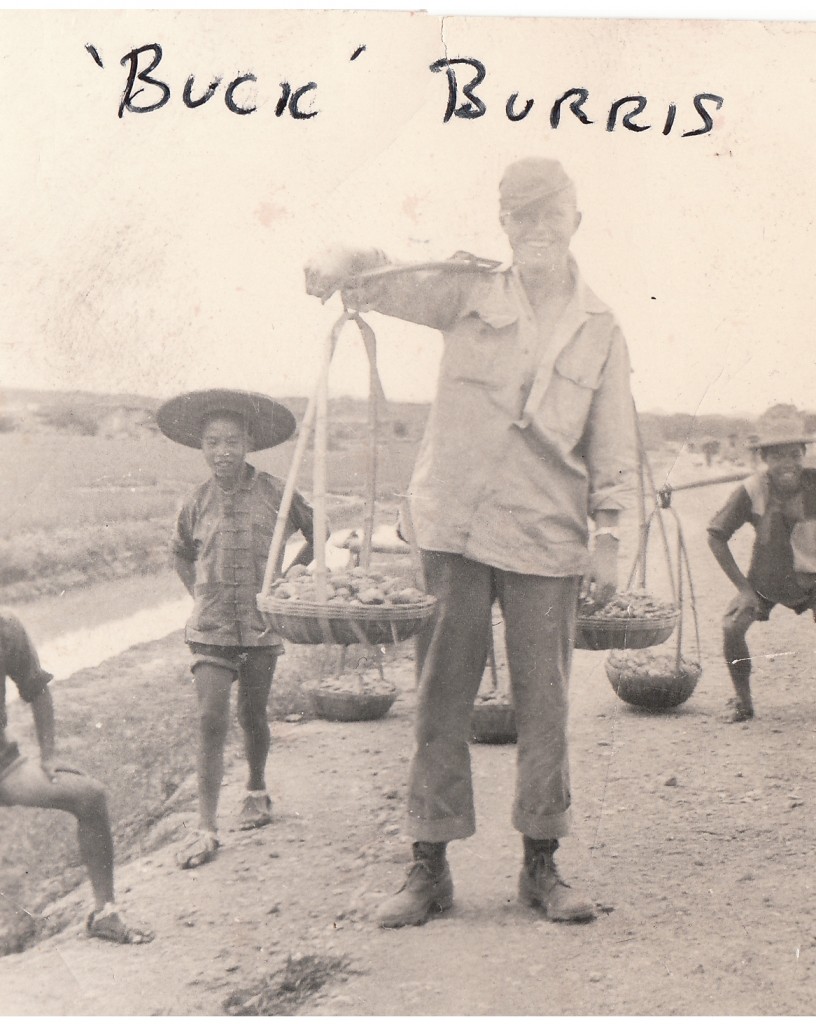

Robert “Buck” Burris passed away last Wednesday, December 5, 2012. He died of liver cancer. He had been fighting it for some time, but if he was discouraged or depressed about it he never showed it. To the end he kept a positive attitude and was a constant source of encouragement for others. His daughter said that he passed peacefully. He was 91 years old. Burris was just a teenager when he enlisted in the Army Air Corps as an aircraft armament specialist. He went to North Africa with the 95th Fighter Group which fought the Luftwaffe for control of the skies with their P-38 fighters. In the summer of 1943, he volunteered to join a squadron destined for China. En route he met Jim Hyde, a maintainer who had been stationed with the 82nd Fighter Group, also in North Africa. Hyde remembered they had bumped into each other occasionally, but not often, until they went to China. “Then we became good friends,” he said. Burris and Hyde were the first two members of the newly-created 449th Fighter Squadron to cross the Himalayas and land in China in July 1943. The two worked hard to set up armament and maintenance functions to prepare the way for the rest of the squadron. Burris and Hyde always seemed to be the advanced guard, moving to a new airbase ahead of the rest of the squadron to get things ready. In a corner of the war without much in the way of equipment and where nothing seemed to go right, the squadron leadership trusted Burris to get things done. The work was dangerous. Burris told me once that since they did not have proper bomb loading equipment, they had to find Chinese laborers to hold the bombs in place beneath the aircraft while he and the other armorers tightened the wing nuts to fasten them in place. They had to worry about frequent attacks by Japanese bombers. Burris had more than a few close calls. Despite ridiculous conditions, Burris told me, “We didn’t think about it, we just did it.” By keeping the squadron’s P-38s armed and in good working order, he and the other ground crewmen were indispensable to the war effort.

Burris returned to the United States in 1945 and left the Army. He told me that he had no direction or purpose in his life and had a rough time. He bounced around from job to job, got married and had a daughter in 1947, but soon divorced. “I was not a bad person,” he told me, “but a bad husband and a bad father.” The truth was that he had grown up in his thirty-two months overseas. His entire adulthood was spent fighting a vicious war and he did not know how to live in peace. He realized that he had a sense of purpose and direction when he was in the military and decided to join the Air Force again in 1956. He was thirty-five. The Army lost his records from China, so even though he was discharged as a technical sergeant, he came back in as an Airman. He went to radar school as Lowry Air Force Base in Denver and was assigned to the 324th Fighter Squadron, whose F-86 Sabres were deployed from Massachusetts to Morocco. Burris worked hard and advanced rapidly, working his way up to Master Sergeant in only eight years. Though he had a rough time after World War II, his second stint in the military set him on the right path. He remarried, this time for forty years until his wife died in 2000. He retired from the Air Force in 1972. At one point he was with his squadron on a training deployment to Vincent Air Force Base in Arizona when none other than Warrant Officer Jim Hyde walked in. Hyde was officer of the day and Burris offered to help him with his duties. Though they had been friends during World War II, they lost track of each other afterwards and the chance meeting in Yuma rekindled a friendship continued until his death. Hyde told me that he was concerned something had happened because he had not been able to get in touch with him recently. “I’ve known him for seventy years,” he said. “We’ve kept in touch with each other for all these years because we were good friends.” He will be sorely missed. God bless him.

Mattie McLaughlin

Mattie McLaughlin

Charlie Burris